What Makes a Storm a Super Typhoon?

When you hear the word super typhoon, you might picture a tornado‑size vortex ripping across the ocean with the force of a Category 5 hurricane. In reality, the label is a product of how different weather agencies measure wind. The U.S. Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) draws a line at 130 knots – that’s about 150 mph or 240 km/h – and anything equal or stronger earns the super‑typhoon tag. It matches a strong Category 4 on the Saffir‑Simpson scale, which many people already know from Atlantic hurricanes.

Other agencies set the bar lower. The Hong Kong Observatory, for example, says a super typhoon starts at 100 knots (120 mph or 190 km/h). Back in the day they even used 115 mph as the cut‑off. The Japanese Meteorological Agency doesn’t use the term at all; it calls storms with sustained winds over 194 km/h “violent typhoons.” The variation comes down to the averaging period for wind data – JTWC uses a 1‑minute average, while JMA prefers a 10‑minute window, which naturally leads to smaller numbers for the same storm.

Regardless of the definition, the physics are the same. A tropical cyclone begins as a weak tropical depression, with winds under 38 mph. As the system feeds off warm sea‑surface temperatures (usually above 26 °C), it can intensify to a tropical storm (39‑73 mph) and then to a typhoon (74 mph+). If the ocean stays warm and wind shear stays low, the storm can keep strengthening until the wind speeds hit the super‑typhoon threshold.

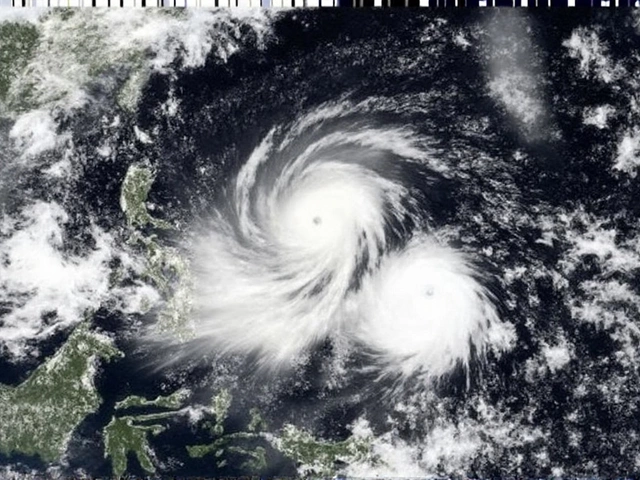

The strongest super typhoons push sustained winds past 240 km/h, with gusts that can exceed 320 km/h. That level of force can rip roofs off houses, uproot trees, and turn ordinary wood into airborne missiles. But the wind isn’t the only danger. The cyclone’s eye, a relatively calm center, is surrounded by the eyewall – a ring of the fiercest winds and heaviest rain. The eyewall’s diameter can be as small as 30 km, meaning the most destructive winds affect a narrow corridor, but the storm’s outer bands can still bring severe rain and flooding far from the eye.

How to Prepare When One Is Brewing

Preparation isn’t about memorizing wind‑speed charts; it’s about protecting lives and property before the storm makes landfall. Below are practical steps you can take whether you live in a high‑risk coastal area or are simply passing through.

- Stay Informed. Sign up for alerts from your national meteorological service, and keep a battery‑powered radio handy. Remember that JTWC, JMA, and local bureaus may issue slightly different warnings – watch the numbers they give and note the averaging period they use.

- Secure Your Home. Board up windows, tighten roof bolts, and clear gutters of debris. If you’re in a flood‑prone region, move valuable items to higher ground and consider sandbagging vulnerable openings.

- Plan an Evacuation Route. Know the nearest shelters, and have a transport plan for pets and family members who may need extra help. Roads can become impassable quickly, so aim to leave before the storm surge begins.

- Stock Essentials. Fill your pantry with non‑perishable food, water (at least one gallon per person per day for three days), and a first‑aid kit. Don’t forget prescription meds and chargers for essential devices.

- Protect Important Documents. Store passports, insurance papers, and birth certificates in waterproof containers or cloud storage.

- Understand Storm Surge. Surge can raise sea levels by 5‑6 m in extreme cases. If official flood maps flag your area as a surge zone, treat any evacuation order as a mandatory directive.

- Stay Indoors During the Peak. Once the eye passes, the opposite side of the storm will slam back with renewed force. Keep away from windows, exterior walls, and structures that could collapse.

Even if the wind never reaches super‑typhoon levels, the secondary hazards can be just as deadly. Heavy rain can dump more than 500 mm in 24 hours, leading to flash floods and landslides, especially in mountainous terrain like the Philippines or southern Japan. Tornadoes, though less common, have been recorded in the outer bands of powerful storms, adding another layer of risk.

Seasonality matters, too. The Western North Pacific’s peak runs from early July through the end of September, when sea‑surface temperatures are at their warmest. During this window, agencies often issue multiple watches and warnings, so keeping the alert channel on can make the difference between a calm night and a night of panic.

Finally, after the winds die down, don’t rush back into a damaged home. Inspect for gas leaks, downed power lines, and structural damage. Take photos for insurance claims and report any injuries or hazards to local officials.

By understanding how a storm earns the super‑typhoon label and following these straightforward steps, you can reduce the chance that a powerful natural event turns into a personal tragedy. The key is preparation before the storm, vigilance during its passage, and careful recovery afterward.